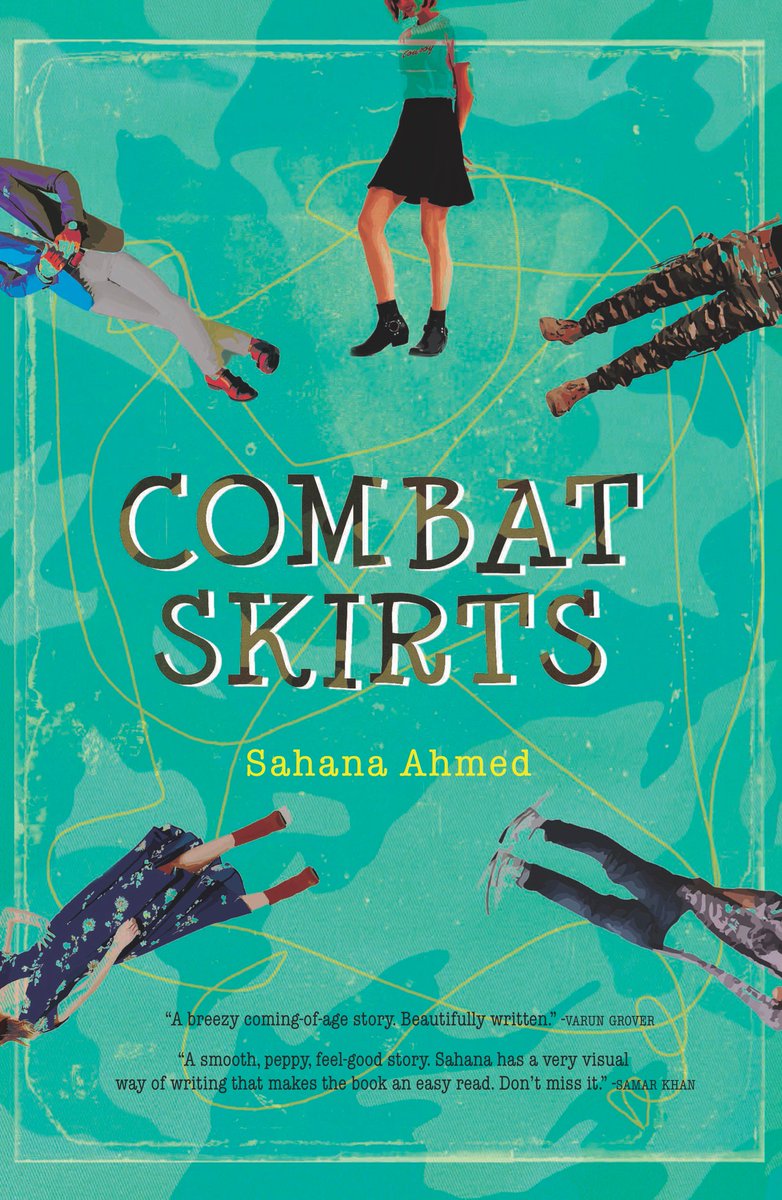

Combat Skirts by Sahana Ahmed: An Excerpt

I had first met Faraaz in Gangtok when he had come home from Mayo for the autumn break. Our fathers were posted in the same Corps and our families moved in the same circles. Especially on Sundays, when the ladies met for Rummy and the men met for drinks. Those were long-drawn affairs, and the children were pretty much left to their own devices.

That Sunday, it had been Shaila Aunty’s turn to play hostess. Mom had dragged me along, to ‘help with the canapés’. One look at Faraaz and I had understood Mom’s intentions.

To be fair, I had found him quite all right. A sure voice, the eyes of a cynic…his presence had demanded more than small talk. We were both the same age, but he was worldlier. He had asked me to call him FMB, that’s what his friends called him, and I had told him I was there on canapé duty.

‘You cook?’

‘Absolutely not! I don’t know what Mom was thinking.’

‘You want to surprise her?’

‘How?’

‘Okay, so what did you have in mind?’ He was already washing his hands.

‘Eggs on toast? Cheese sticks?’

‘Boring! Let’s see what else we have here.’ He was scouring the pantry before I could feel properly insulted.

The kitchen was big but still narrow for two people. I had limited myself to the spot near the sink and let him do all the hard work. He had handed me a packet of Lijjat papad and showed me how to roll them. ‘Like little party hats.’

Dhaniya, nimbu, saunf, the air had turned delicious, but I had focussed on my hats. I hadn’t wanted to disappoint him.

The salsa papads were a smash hit. Faraaz had let me take all the credit, and Mom, who had been losing so badly at cards, couldn’t manage to lose her grin. She was probably getting visions of Faraaz serving me breakfast in bed.

Before the day was up, I had learned that Faraaz could whistle like a pro and play a mean game of Checkers. That he liked Boris Becker and hated Bayern Munich. That he listened to Led Zeppelin and collected vintage kukris. I had learned that he could wolf down a full casserole of chicken all by himself, bones and all.

He had given me a tour of the house and taken me around the garden. He had plied me with orange squash all afternoon, to reveal later that the bathrooms were haunted.

He had amused me. I had wondered if he was gay. I mean, I was a girl, he was a boy, and yet he was so normal. The boys in my class were idiots. They cried ‘Shiv, Shiv!’ if a girl so much as crossed their paths. This one was different. Maybe he was cool because he was from a boys’ school. Maybe they had classes on how to behave with the ladies.

Before I had left his house, Faraaz had asked if we could meet again, he had wanted my opinion on some pictures he had taken. ‘I haven’t shown them to anyone,’ he said. ‘Not even to my friends, those clowns have no aesthetics.’

‘How do you know I’m better?’

‘Look at you,’ he had pointed at my parrot-green sweater. ‘Only someone with style can carry that off.’

There, he had done it again. Insulted me, applauded me. I had never met someone like him, I couldn’t wait to see him again.

***

It was the first time in my life that a boy had asked me out, and even though no one was calling it a D-A-T-E, I had wanted to look my best. Which is why I wasn’t going to take a chance by wearing a Mom-made sweater. The angora cardigan she had wanted me to wear made me look like a giant bunny rabbit, and so, I had lied. ‘Faraaz wants to take pictures.’

‘Your pictures?’

‘My pictures.’

Mom had rushed to her cupboard and taken out the new tweed jacket she had bought me from Kalimpong. ‘Wear this.’

‘But Mom, that’s for Christmas!’

‘Shut up and wear it.’

I was thrilled. There was guilt in my heart, but it was washed clean by the pop-pop-pop of anticipation. It was a beautiful day!

Faraaz met me at the helipad. The first thing he had done was to look at my shoes. ‘Oh good, we can walk to the fair.’ Okey-dokey, I had said.

We had walked in silence, the fluttering of prayer flags the only sound. There was no traffic, just us, broom grass, and the wide-open sky. The wind was high and Mom had asked me to carry an umbrella, but I had ditched it at the garden gate. It would have ruined my look. Speaking of which, Faraaz had made no effort to dress up. He was in the same United Sikkim jersey I had last seen him in. I had felt a little cheated.

‘Who writes those?’ He had pointed at a roadside sign: IT IS NOT RALLY, ENJOY THE VALLEY.

‘I don’t know, I’ll ask my friend. Her dad is with the Border Roads.’

‘She’ll be at the fair?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Is she pretty?’

‘Don’t be silly, road is hilly.’

The boy from Mayo had cackled like a hyena. I liked him.

***

Shaila Aunty excused herself to get the telephone.

She had a lovely drawing room, prettier even than Gangtok. The curtains were organdie with little French knots, and there was a new silk rug. Her Dhulabari crystals had made way for coffee-table books, and Faraaz’s photographs had pride of place in the foyer. Aunty was that rare fauji lady who understood restraint.

I walked to the balcony. Chrysanthemums and ferns, and a glass wind chime. A gentle breeze played with the flare of my skirt. I could see the hostel from there.

‘Aren’t you scared!’ he had screamed.

‘Not of the mountains!’ I had answered.

His photographs had slipped my fingers and I had bounded down the hill to catch them. The mission had left me with leeches on my socks but at least his pictures were good. Leukoplast on a cracked egg. Doughnuts on a bathroom scale. An India-shaped pothole. I was impressed.

I had let the leeches feast on me, it was safer that way. He had whistled a pahadi dhun, and the Kanchenjunga had turned pink in the gathering dusk. I had had quite a day.

We had made heads turn, Faraaz and I. He was great arm candy. We had played shoot-the-duck and whack-a-mole and binged on free samples of rhododendron jam. We had gone from stall to stall lip-syncing to Anu Malik songs, and for lunch, we had shared a pizza, agreeing to not tell anyone it had bacon on it. I had introduced him to chhurpi, and he had said it was better than ricotta. I had no idea what that was, so I had said, ‘Absolutely!’

The walk back home was steep. It was his idea to get a taxi. I had never taken a taxi before, so I had said no, but he had asked me to relax and run off, and found us a van. Two seats for the price of one, he had beamed. I had climbed into the front, for the back was packed, and when I had wondered where Faraaz would sit, he had slid in right next to me. It had happened in an instant, the shock of contact with his body. His thigh against my thigh, his arm against my arm, his warm chhurpi breath on the side of my face. I was fourteen; I was not ready to be touched yet.

It was a long, winding road to Tadong. I had sat there, not breathing, not moving, trying my best to not betray to the boy next to me I had lost all magic for him. We had parted awkwardly. It was sad.

***